Blue Bikes, and urban transformation

Walking between the small paths around the Boston Commons, families taking bikes from the bike station by the entrance, squirrels running around the park, it is just the way to enjoy a sunny summer day. Having accessible bikes to take from anywhere around you makes it much easier to enjoy without worrying on how to move from one place to another. With all the craziness, busy streets, and the hectic public transportation in the big cities bicycles are always a good way to get fast to your destination. Bike sharing is relatively a new concept that was introduced in the 1960s staring in the most bike friendly city, Amestrdam, Netherlands [2]. The main purpose and idea behind it was to have bike stations around the city for anyone to rent a bike for the amount of hours they need, mainly for people who are not able to afford buying a bike or do not have the space to store their bikes or even people who just use the bike as a change from time to time. The bike sharing concept made bike usage very easy, where you can take a bike from a station to you destination and then leave their for someone else to use. This concept reduced car utilization to 20-30% in most cities in the United States and Europe [1]. Bike sharing is a new form of mobility to urban landscaping, it brings in a similar idea to the car sharing methods, Lyft and Uber. These new methods are all changing the norm in urbanism and how things used to be regarding transportation. They are all making the transportation methods easier, accessible to everyone, and reducing the hectic and busy life in the big cities.

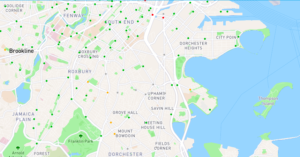

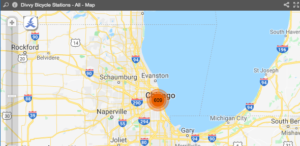

Bike sharing was then moved to the United States in the 1990s, starting off in the capital, Washington DC. When the other big cities saw the success of the bike sharing concept and how it reduced the usage of cars and created less hectic environment, they then started implementing it in their cities. New York was the second to implement, followed by Chicago, Detroit and Boston was one of the last cities to bring in the bike sharing concept. As of now there are more than 42,000 total bikes located in different states around the US. Boston started “Hubway” which now is called Blue Bikes in 2011, with 600 bicycles in 60 stations around Boston then expanded it to be more than 300 stations today, around the Boston area [4]. Most of these stations are heavily located in the “city” or in other words where most of the workplaces, universities, residential areas, and restaurants are, as you can see in figure 1. Blue Bikes also try to put their stations close to historical and touristy places; such as parts of the Emerald Necklace to make the renting process for Boston visitors and have an “adventure pass” for $10, for a 2-hour unlimited rides mainly for individuals visiting the city. These bikes are put at low prices so they can be accessed and affordable to everyone and to people from different classes in the society, a single trip can be as low as $2.50 and annual pass with unlimited rides costs $99/year [4].

Figure1: map of the northern part of the Boston area

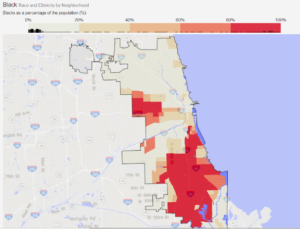

In Boston, the Blue Bike stations are not put in the poor areas and the places where a lot of people of color live such as; Roxbury, Jamaica Plane and Dorchester as shown in figure 2 below. Organizations like Blue Bike, do not consider areas like these because they are scared of theft and putting stations in areas like these are “most likely to be stolen”. “ The Color of Law” is a book written by Richard Rothstein that talks about the segregation the United States government made in the housing system and what type of people can live where. In one of the chapters he mentions that in some of the housing organizations and authorities like the Tennesse Valley Authority (TVA) they would say “Negros do not fit into the program” [Rothstein, 19]. I would relate this saying to the Blue Bikes distribution in the Boston area and how they are less spread in the black neighbourhoods. Although these areas have a lot of historical spots and places to visit and see, they are not given enough attention from Blue Bikes. In “Bike-share Still Has a Race Problem” by Huth L. and Salem T., say that in Chicago, Boston, and DC, bike sharing stations tend to be more in wealthy- white neighbourhoods and less in poor black areas [3]. The Blue Bike stations in the poor areas in Boston are not as maintained as the other stations around the city. The number of bikes in each station there is also less than the number of bikes in the other stations.

Figure 2: map of the southern part of the Boston area

As you walk around the city of Boston you can see the Blue Bikes stations located everywhere. You can easily find stations around the Back Bay Fens, Boston Commons, popular churches, big parks such as the Franklin park, and around residential areas. Having this easy accessibility to the bike stations make individuals use them more. I myself, in most of the summer days and when the weather's nice, I like to rent a bike for at least a half hour from the Fenway station located next to my building and just bike around the area or the Back Bay Fens.

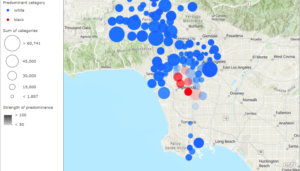

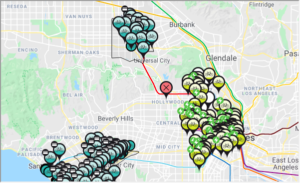

Although Blue Bikes and bike sharing in general try to make it easy to transport from one place to another, yet they still contribute in forming a social segregation gap in cities in the United States. These programs tend to serve a specific race and social class individuals. In Chicago, Illinois, for example, as you can see in figure 3, 80% of the bikes are put in stations that are accessible to white chicagoans [6], many of higher income individuals compared to their black counterparts. The same is in Los Angeles, California, the overdependence on driving in the black neighbourhoods compared to the rich neighbourhoods is most likely because of the lack of accessibility to bike sharing stations as you can see in figure 4 [6].

Figure 3. Black population in Chicago vs. where bike-sharing stations are located

Figure 4. Black population in Los Angeles vs. where bike-sharing stations are located

All in all, these programs are touted as an excellent way to limit car emissions while imultaneously providing a healthy mode of transportation for urban populations. However, they are increasing the social gaps created in societies because of the stereotypes of the black neighbourhoods and how they are rated high in crimes and thefts. Some adjustments has to be done in order to create equality in the station distribution of the bikes around the cities. In this story map, you be able to see the different distributions in the different areas around Boston.

References:

[1] Fishman, Elliot, et al. “Bike Share’s Impact on Car Use: Evidence from the United States,

Great Britain, and Australia.” ScienceDirect, Aug. 2014,

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1361920914000480.

[2] “Bicycle Sharing.” Active Transportation and Real Estate: The Next Frontier,

https://uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/Bicycle-Sharing.pdf.

[3] “Bicycle Sharing.” Active Transportation and Real Estate: The Next Frontier,

https://uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/Bicycle-Sharing.pdf.

[4] “Everything's Better on a Bike.” Bluebikes, Motivate International Inc.,

https://www.bluebikes.com/.

[5] Lambert, Tim. “A BRIEF HISTORY OF BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, USA.” Local

Histories, 2019, http://www.localhistories.org/bostonus.html.

[6] Small, Chad. “These Black Neighborhoods Aren ’t Getting Any Love From Bike Share

Programs.” Blavity:News, Nov. 2019,

https://blavity.com/these-black-neighborhoods-aren-t-getting-any-love-from-bike-share-programs?category1=news&subcat=Environmentalism.

[7] “Bike Share in the US: 2010-2016.” National Association of City Transportation

Officials, May 2018,

https://blavity.com/these-black-neighborhoods-aren-t-getting-any-love-from-bike-share-p

rograms?category1=news&subcat=Environmentalism.

[8] https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/890

[9] “Back Bay Fens.” Emerald Necklace Conservancy,

https://www.emeraldnecklace.org/park-overview/back-bay-fens/.

[10] “Fenway Park.” StadiumsofProFootball,

https://www.stadiumsofprofootball.com/stadiums/fenway-park/.

[11] “Boston Common.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_Common.

[12] “THE CHARLES RIVER PATHS.” Great Runs,

https://greatruns.com/boston-the-charles-river-paths/.

[13] Vadum, Arlen. “A Short History of Boston's Beacon Hill.” Beacon Hill,

http://www.beacon-hill-boston.com/History.

[14] “HISTORY OF THE OLD STATE HOUSE.” Old State House ,

https://www.bostonhistory.org/osh-history.

[15] “Beacon Hill Demographics .” NICHE ,

https://www.niche.com/places-to-live/n/beacon-hill-boston-ma/residents/.

[16] “Boston Harborwalk.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_Harborwalk.

[17] Rios, Simon. “Are The Red Sox Turning The Corner On Race? It's Complicated04:36

Play October 26, 2018.” WBUR News, 26 Oct. 2018,

https://www.wbur.org/news/2018/10/26/red-sox-racism-reconsidered.

[18] Johnson, Martenzie. “THE SEARCH FOR BLACK RED SOX FANS AT FENWAY

PARK.” The Undefeated, 4 May 2017,

https://theundefeated.com/features/black-red-sox-fans-fenway-park/.

[19] “Bunker Hill Monument.” National Park Service,

https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/bhm.htm.

[20] “The Southwest Corridor Park: A Neighborhood's Response to a Highway.” Jamaica

Plain Histprical Services,

https://www.jphs.org/events/2019/7/28/the-southwest-corridor-park-a-neighborhoods-response-to-a-highway.

[21] “Southwest Corridor Park - History.” Southwest Corridor Park,

http://swcpc.org/history.asp.