By Andrea Aponte

A result from both past and present processes, urban landscapes tend to change dramatically over time. As these landscapes evolve, the narratives that communicate the effects of these processes are often ignored and unrecognized, even by the very people who interact with that landscape on a daily basis. The purpose of my StoryMap is to uncover these narratives. Utilizing a series of visible and nonvisible histories from 12 separate geographic locations, my exhibit explores the predominately racialized and segregated narrative that presently exists in the community of Jamaica Plain.

To anyone who has explored both the Washington Street and the Centre Street sides of Jamaica Plain, the difference is largely visible. Over the years, these two separate regions have become increasingly contrasted, both socially and economically, despite both nominally placed within the boundaries of Jamaica Plain. This contrast allows the regions to exist as relatively independent from one another, as if two separate and segregated hemispheres inhabiting one greater space. It is this particular contrast that my StoryMap intends to illustrate. Starting at Franklin Park, my exhibit will explore how the forces of urban segregation have manifested on the Washington Street hemisphere through discussions on transportation, gentrification, and a series of discriminatory practices executed by the federal government. Following these discussions, my StoryMap will embark on a gradual transition into Washington Street’s social and economic counterpart: Centre Street. Here, my exhibit will consider the forces that have allowed this opposite hemisphere of Jamaica Plain to exist under the circumstances it does today, mainly through discussions on residential development and access to green spaces.

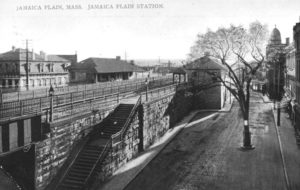

To help visualize this racialization, I will utilize two of Jamaica Plain’s most frequented passages: Green Street and the Southwest Corridor. Green Street’s continuously evolving landscape provides a unique window into the “patterns of change” that have occurred throughout Jamaica Plain. Laid out in 1836, Green Street existed as one of the first commercial ventures in the surrounding area. The street has also historically provided access to major local transportation services, starting with the Boston and Providence Railroad Company and ending with Boston’s MBTA. Its commercial and transportation popularity contributed to the significant population growth noted in Jamaica Plain beginning in the late 19th century, which attracted both wealthy homeowners and working-class immigrant families. As residential expansion increased in subsequent decades, a pattern of development was adopted, establishing the different trends we experience along Green Street today. Generally, neighborhoods to the east of Green Street (near Washington Street) are associated with lower-income, racially diverse factions actively battling the increasing forces of gentrification. Alternatively, as noted throughout the tour, neighborhoods to the north and west of Green Street (near Centre Street) are commonly associated with upper-middle class, garden suburban residences given heightened access to retail diversity and green spaces such as the Emerald Necklace. By historically supplying the means for commerce, transportation, and residency, Green Street occupies the role of effectively linking the Washington Street hemisphere with the Centre Street hemisphere. As articulated throughout the various stops on my StoryMap exploration, this connectivity between two opposite spheres can be interpreted as an evolving and visible gradient.

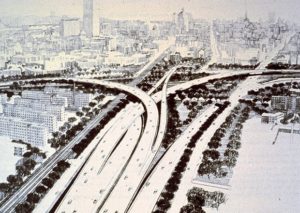

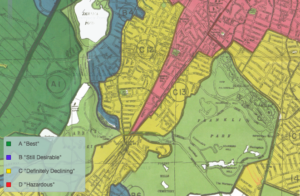

In a similar manner, the Southwest Corridor plays a large role in actively reinforcing this dialogue of racialization within Jamaica Plain. Much like Green Street, the Southwest Corridor encompasses an evolving history shaped by a series of past and present processes. Before it was the linear park we experience today, the Southwest Corridor was the potential site for an eight-lane, mostly elevated extension of the I-95 highway. Proposed in 1948, the highway extension was intended to run through the Hyde Park, Egleston Square, and Roxbury communities of Jamaica Plain. After years of organized opposition and grassroots mobilization, the people of Jamaica Plain successfully halted the construction of the bypass. Instead, the Southwest Corridor was granted to the community; construction began in 1977. Since its establishment, the Southwest Corridor has facilitated a series of urban dynamics that have forever remained a part of Jamaica Plain’s social fabric. These dynamics can be attributed to the park’s unique placement between Lamartine and Amory Street. When observing the redlined maps published by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934, one will notice that Amory Street, the westernmost boundary of the corridor, is also the easternmost boundary of the red-lined region in Jamaica Plain, namely Egleston and Roxbury, denoting a “hazardous” and “undesirable” region. Whether this placement was intentional or not, it has fostered a visible divider in a region otherwise invisibly separated.

The discourse regarding the Southwest Corridor as a visible divider and Green Street as a connector is further explored throughout my StoryMap. By highlighting the physical and non-physical differences that are present on the opposite sides of the linear park, I present an understanding of the Southwest Corridor that considers its role as the “unofficial, official” border between the two separate hemispheres of Jamaica Plain-- with Green Street as an active gradient between the two. Establishing this context allows one to further explore the dynamics brought upon by the corridor, especially in regards to The Emerald Necklace. On the Washington Street hemisphere of the Southwest Corridor, residents are granted easy access to Franklin Park; on the Centre Street hemisphere, residents are granted access to the Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Pond, and the entire remainder of the Emerald Necklace (as a reminder, Washington Street is largely lower-income, and Centre Street as generally middle-high income). This discussion reflects upon a common pattern seen in urban spaces everywhere that juxtaposes affluence with access to green spaces.

The ultimate goal of my StoryMap tour is to uncover these forgotten and invisibilized narratives. A result of continuously evolving histories, these narratives help foster an understanding of the racialization we experience throughout the Jamaica Plain landscape. They are very important for not only articulating this understanding, but also for providing a comprehensive account on the impacts that these forces may have on a single community.

Sources Used:

https://www.jphs.org/transportation/orange-line-memories.html?rq=orange%20line

https://www.jphs.org/transportation/people-before-highways.html?rq=people%20before%20highways

https://www.jphs.org/locales/2017/11/13/history-of-the-development-of-green-street-1836-1900?rq=segregation

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=15/42.3098/-71.1051&opacity=0.8&area=D8&sort=221&city=boston-ma

http://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1970s-present-Local-Land_use-Regulations.html

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=4/36.71/-96.93&opacity=0.8

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2012/10/17/11-cool-photos-original-orange-line/

https://hyperallergic.com/238667/artists-and-activists-trace-bostons-historic-red-line-on-the-streets/