The City and The Green Space

Access to open space, especially when it comes to public gardens, is an important piece of figuring out how urban landscape works on a larger scale. In reviewing locations that have been created, and perhaps have since disappeared, it’s easy to see which social groups have been targeted in denial of access and what structures have been deemed more important than allowing space for plant growth. Along the Emerald Necklace locations such as Roxbury have lost garden spaces1 while others like Deer Island had homes torn down to make room for open space.2 The question is what separates these locations from others, like the Trustee Gardens of the Southwest Corridor,3 which are more successful in being equally beneficial to all?

Several factors play a part in determining what the city views as useful or, instead, an unnecessary project to upkeep. There are a few that many people would immediately think of, such as a lack of funding or a change in the organization’s goals. The loss of the Roxbury Canal Rose Garden was a victim to both. In the 1800s William Doogue, the Superintendent of Common and Public Grounds at the time, build the garden to expose residents to the joys of gardening, but his death brought around a change in power and more strict funding regulations.

This project turned into the Boston Medical Center, now including the Rooftop Gardens.4 In reviewing the shift from utilizing an entire plot for open space to balancing it between working space as well, the urban landscape is shifting to realize the importance of green space in a densely built environment.

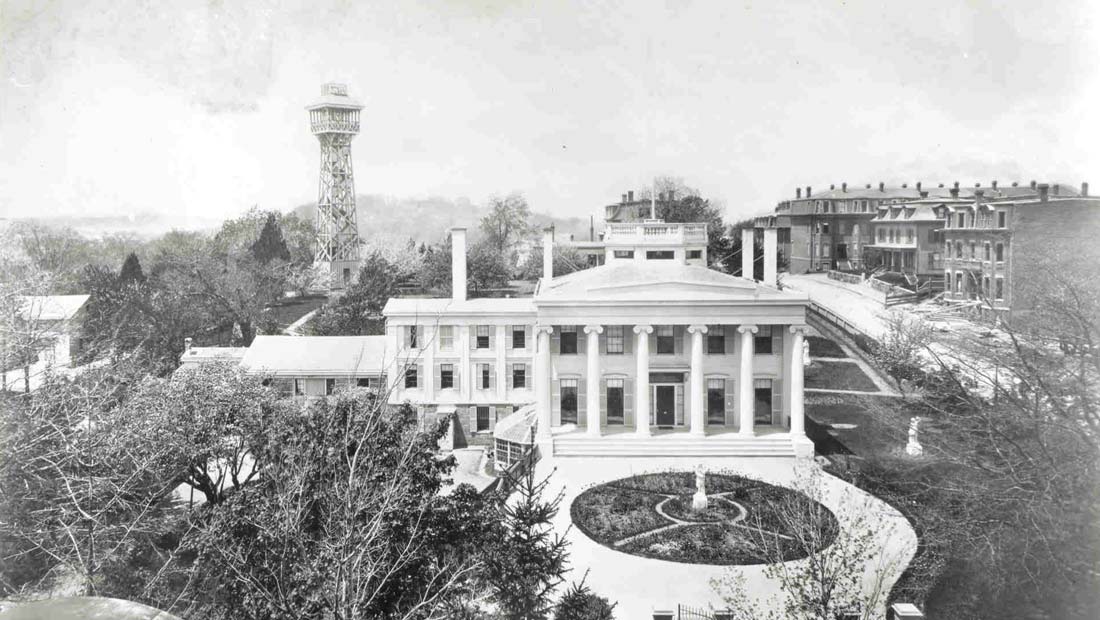

The city’s shift to prioritizing the existence of green space in urban areas is best shown through The Trustees of Reservations.5 The Trustees is an organization focused on protecting and sharing green and historic spaces with the people of Boston and organizes information on fifteen acres of community gardens in the Boston area. These fifteen acres are divided throughout the city into 56 community gardens, nine in Roxbury alone. The Trustees played an instrumental role in the restoration of the Alvah Kittredge House and attached garden.

Alvah Kittredge was the politician and businessman responsible for the development and annexation of Roxbury by the city of Boston. The gardens attached to the garden have since expanded to include the Allan Crite Community Garden, named for Allan Crite, a Black artist who commonly depicted the nonexistent Black middle class to promote the idea of Black people as part of American society rather than a satellite to it.6 The Trustees directs the residents of Boston to green spaces located in and around the Emerald Necklace, as well as directing people to the diverse communities that support these gardens.7

These just mark two examples of how access to green spaces is vastly different and varies by how those in power view the importance of the community surrounding the site as well as how their views shift over time. However, analyzing these spaces show that smaller, public garden spaces provide intimacy in a way that larger green spaces fail at. Communities are built in spaces that they create and take ownership of; denying possible users access to those opportunities causes the space to fail.

Photos: Boston Medical Center Rooftop Garden plots, Alvah Kittredge House ariel view, Allan Crite Community Garden connecting path to Kittredge House

A Look Into Bostonian Gardens

This Garden Walking Tour will explain how these gardens work for or against community development. Each location has its own history that has led to its current position in the Boston area, determining what benefits it offers to its visitors. Through this map, you will hopefully come to understand what these sites offer and how each community has come to claim it as their own, or in some cases have fallen second.

All these sites are integral to the sense of community through their historical ties to Boston and what they offer functionally. Without green space, the fabric of cities would lack the life it has today—a truly gray scene otherwise.

Responsibility to Community

According to the Natural History Museum, “We have a responsibility as human beings to take care of nature in our cities.”8 The Emerald Necklace and surrounding gardens give Bostonians a reason to gather and produce something as a community that upholds that statement. The spaces are vital to the inhabitants of the city; reviewing Boston green spaces claimed by the communities around them, as well as how the people have come second to such spaces, demonstrates their weight.

As Olmsted designed it, the Necklace connects each of these local garden sites to create an overarching network of greenery for neighborhoods to collaboratively enjoy. Over time it has become, in its own way, a museum as well. It’s become a time capsule that shows how access to green spaces has allowed communities to come together and develop pride for their neighborhood; each site has its own rich history that developed into the beautiful experience seen today.

Of course, this comes with a price—one usually paid for by the lower class. While not in Boston, a primary showcase is the tragic loss of Seneca Village in the case of Central Park, New York. Olmsted created a great getaway from the busy city, but at the whim of the surrounding White, rich communities who wanted the thriving Black community out.9 This has to be recognized as a flaw in the current push for green space.

Allowing smaller, low-income communities to receive the benefits from having access to gardens helps improve their way of life incrementally. It allows them to produce food at low costs and allows them more space for activities, especially as more high-end residences and businesses take more area from cities. Not only that, but it stimulates connections between other gardeners across the city through a shared hobby, regardless of other factors.

In light of this knowledge, it has to be amended that people have not only a responsibility to nature, but the communities in which nature is being upheld for. Access to green space is not a privilege only to those who can afford it, but an opportunity to improve the lives who struggle otherwise.

Composed by Elena Mercurio & Avery Gilloren

References:

1 Andersen, Phyllis. “The Art of Planting: The Gardeners of Boston’s Public Garden.” Friends of the Public Garden, Boston, MA. 16 Oct 2020. friendsofthepublicgarden.org

2 “History: Deer Island.” MWRA, Boston, MA. Fall 1999. fbhi.org

3 “A Tapestry of Community Green Spaces” The Trustees, Boston, MA. 2020. thetrustees.com

4 Andersen, Phyllis. “The Art of Planting: The Gardeners of Boston’s Public Garden.”

5 “Preserving Exceptional Places.” The Trustees, Boston, MA. 2020. thetrustees.org

6 “Allan Crite” Hi So You Are. hisour.com

7 Jr, Sam Bass. "To Dwell Is to Garden." Northeastern UP, 2019. Repository.library.northeastern.edu

8 Mair, Callum. “Why We Need Green Spaces in Cities” Natural History Museum, London, UK. 2020. nhm.ac.uk