Every newcomer to Boston hears the same legends of how the city was built up from a small, unimportant peninsula in a swamp to a bustling metropolis. How an untamed wilderness of forested mountains was torn down for human settlement, how the soil from that wilderness was used to bury the noxious swamp underneath gridded lines of row houses, and how Frederick Law Olmsted brought it back with his carefully engineered park system. The artificiality of Boston’s landscape is common knowledge, but rarely spoken about besides an occasional “oh, that’s cool”. We like to think that these projects are solely historical events and are just part of the landscape now as any natural formation would be. But their construction still has effects on the city today. They can act as barriers between people or magnets that bring them together, and their initial construction and continued existence has defined the areas around them for generations.

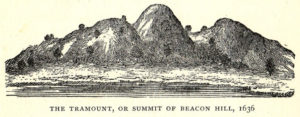

The history of Boston’s expansion begins in 1630 when Reverend William Blackstone, a priest from the nearby Charlestown, then the capital of the English colony, set off to begin “dwelling on the other side of Charles River, alone, at a place by the Indians called Shawmutt.”1 It was a small peninsula of about 789 acres or 1.23 square miles, nearly 90 times smaller than the city is today. The peninsula was dominated by hills and forests, nine hills overall and three much larger ones known as the Trimountain (the namesake of Tremont Street). The peninsula was connected to the mainland of the neighboring settlement of Roxbury by the Boston Neck, a 120 foot wide isthmus that is now Washington Street. Boston’s history of designing landscapes can be divided into a few major periods, the first being from 1630-1807. During this time, there were smaller-scale projects that laid the foundations for much larger ones to come. The core areas of the city began to be settled and the land flattened, parts of the Charles River were dammed off, and the artificial landscapes of Boston Common and the Arnold Arboretum began to take shape. 1807 marks the first major reclamation project, the filling in of Mill Pond and the Great Cove using soil from Copp’s Hill and the Trimountain. 1814-1900 was the period of time during which the Back Bay was filled and most of the remaining hills were flattened. It was crowned with the completion of the Emerald Necklace around the turn of the century, and represents a transition to focusing on rehabilitating existing land. The 1900s and early 2000s were dominated by such projects, including urban renewal programs that created Government Center and the Federal Highway System and the creation of new parkland and revitalized neighborhoods in places like the Southwest Corridor, Fort Point Channel, and Craigie’s Bridge.

In her 2013 essay Relational Landscapes: Material Portraits of New York City and Elsewhere, landscape architect Jane Hutton argues that our analysis of designed landscapes should take into account where the material came from and the effects the movement of the material had on it. Additionally, any number of changes at the destination could have ripple effects for the origin. One example Hutton uses is the construction of Central Park, which originally used granite quarried in Maine but was soon forced to get it from local stonecutters after a law was passed to protect them from “competition with cheap labour in Maine”. This was a boon for New York artisans, but severely hurt the Maine quarrying industry. Soon enough, Maine went from the largest exporter of granite in the nation to just another quarrying state.² We can use this same strategy in Boston on a much smaller scale. Building land to fill in Mill Pond will invariably have an effect on Copp’s Hill, where the soil came from, and not just because the hill got smaller. Making and taking land both have political, social, and economic repercussions, and understanding their interactions is crucial to understanding the history of Boston. Taken all together, all of the designed landscapes form a massive web of connections that gives insight into broader issues and concepts about the city such as how and why racial and socioeconomic disparities exist and how Boston’s culture formed in the way it did.

Even landscapes that no longer exist or are severely overshadowed by other things exert their influence. From former dams to former highways, structures that have been long since demolished, filled in or otherwise destroyed still leave their marks and often pave the way for new designed landscapes to take their place. One example of this is the “Master Plan”, a massive undertaking to construct federal highways in and around Boston. One such Highway, the Southwest Expressway, was met with such fierce protests that the project was cancelled midway through. The result was a long, narrow stretch of barren land that was cleared to make way for a highway that would never come.³ Another part of the highway system, the John F. Fitzgerald Highway, actually existed until 2008 before being redirected underground. Both of these highways now destroyed left a permanent mark on the city. Their footprints’ awkward shapes meant that it would be impossible to redevelop them as normal housing and act as if nothing happened, so a more creative solution was needed. In 1978 and 2008 respectively, the Southwest Corridor Park and Rose Kennedy Greenway were built. So, in a way, the highways live on today. A much more subtle example of this is Beacon Street in the Back Bay. It was once the site of a dam, and quickly became a tourist destination and public gathering place. Although the dam no longer exists, it is still a major public thoroughfare used much in the same way it was a century and a half ago. It is also a particularly expensive part of the already expensive neighborhood, calling back to the days when it was a highly sought after waterfront property.

These designed landscapes and their histories are all integral parts of how we experience Boston today, and all too often we overlook the lessons they can teach us. Anne Whiston explains in her 1996 essay Constructing Nature: The Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted that if we are unable to recognize designed landscapes “as an artful, deliberate reconstruction of landscapes laid waste by human occupation, [it] blinds us to the possibility of such transformations elsewhere.”4 Going forward, we will have many more opportunities for reconstruction if we choose to take them. It is unclear how any of the designed landscapes we have today will hold up to the elements. There are concerns about the stability of building foundations on the “made land”, including in the Back Bay where many older homes are built on wood pilings. Decreasing groundwater levels, like Boston is experiencing due to a variety of factors both natural and anthropogenic, are concerning because exposed wood will start to deteriorate, causing instability in the buildings.5,6 In a similar vein, rising sea levels also threaten coastal cities like Boston, and it is possible that with the projected rise by 2100, “the city would look a lot like it did in the time of George Washington”. Some have proposed constructing canals like those of Venice or Amsterdam in order to mitigate flooding.7 The city also has a significant amount of green coastline, mostly constructed but some protected natural coasts, which also help slow the advance of water. Venice and Amsterdam, like Boston, are predominantly designed landscape. In order to combat 21st century problems, these cities may need to call upon the ingenuity and creativity of landscape architects once more.

Notes:

- Horsford, Eben Norton, The Indian Names of Boston, and their Meaning, John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, MA, University Press, 1886.

- “Reciprocal Landscapes: Material Portraits in New York City and Elsewhere.” 2013. Journal of Landscape Architecture. 40-47.

- Jim Vrabel, A People’s History of the New Boston (Amherst: UMass Press, 2014), 139-149.

- Anne Whiston Spirn, “Constructing Nature: The Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon (NewYork: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), 91-113

- Stoll, Amanda. 2018. “Underneath Boston: A City Built on Wood Piles Preserved by Groundwater – NorthEndWaterfront.Com.” NorthEndWaterfront.Com. September 27, 2018. https://northendwaterfront.com/2018/09/underneath-boston-a-city-built-on-wood-piles-preserved-by-groundwater/.

- Thys, Fred. 2016. “Continued Drought Spells Concern About Building Foundations In Back Bay | Morning Edition.” Wbur.Org. WBUR. October 31, 2016. https://www.wbur.org/morningedition/2016/10/31/drought-back-bay.

- Jolly, Joanna. 2014. “How Boston Is Rethinking Its Relationship with the Sea.” BBC News, October 27, 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29761274.