StoryMap

Reflective Essay

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

EDGAR DEGAS

Edgar Degas, an impressionist painter in the late 19th century, has inspired me both as an artist and as one who observes art. Growing up in Washington D.C. while under the influence of my artist mother, I was often dragged from museum to museum at a young age. My brother and I would run past the rows and rows of paintings and sculptures, paying them little attention. As I grew older, my long strides turned into slow, relaxed steps and I began to pay more attention to the works around me, noticing the details, exploring the lines, shapes, and colors, and interpreting their meaning. My growing interest soon developed into a passion and I started taking art classes and visited the museums of the Smithsonian Institute. I found that art is not what the artist sees, it is also how the art presents a new opportunity for interaction and community.

However, throughout my time in this class, I have realized that my engagement with the art community and visits to museums have been one that not a lot of people share. Not only do museums serve to create or link communities through educating and entertaining the public, they also have the opportunity to divide them. I have discovered that racism and segregation has been woven into the history of museums and you can even see it while walking through the corridors. I have noticed a lack of cultural inclusion and diversity in its art, visitors, structure, and the neighborhoods surrounding it. By exploring some of Boston’s world-class museums, we can look at how they have divided communities and whether or not they’ve made the effort to be more inclusive. We must ask ourselves: how did this happen, why did this happen, and why is it still happening?

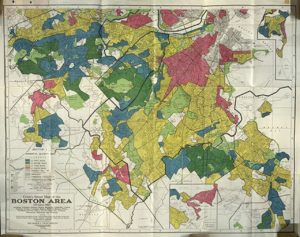

One of Boston’s most famous features is the Emerald Necklace, the 1,100-acre chain of parks running through the center of Boston and into the greater Boston area. The Back Bay Fens, a link in the Emerald Necklace and home to several of Boston’s famous museums, is where my walking tour begins. The story begins here when Isabella Gardner and her husband Jack became interested in the land around the Fens. Jack, who was on the board of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, may have been aware that the area would eventually be a cultural center. In 1899, both Gardner and the MFA purchased the land in their respective current locations. Since then, the area around the Fens has undergone major developments, contributing to the segregation of the neighborhood around it. These changes can be seen by examining a redlining map of the area. A redlining map is a map created by the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation that warned lenders away from neighborhoods that were potentially risky for investing and highlighted other areas as “safe” determined by the neighborhood’s demographics. Today, we can examine a redlining map to identify the racial makeup of a neighborhood. The MFA, the Gardner museum, and the Back Bay Fens all sit almost immediately on the line between an area characterized as a predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood and an area characterized as a predominantly black, poorer neighborhood. This lay the foundation for the segregation of the neighborhood that would be seen even a century later. Today, not only are the neighborhoods around museums segregated, but segregation also occurs inside the museum walls.

Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law explains how a lot of the racial segregation taking place in our neighborhoods is a result of de jure segregation, the isolation of African Americans through federal, state, and local policies. One idea that Rothstein illustrates is how in many cases, white Americans did not want African Americans moving into their neighborhoods because it would look bad and would lower housing prices in the area. The same idea can be applied to museums. The racial composition of neighborhoods surrounding museums made up mostly of rich, white Americans can be explained because museum administrators wants to be located in areas that appear friendly, clean, and wealthy because it makes it more likely for visitors to want to come. As a result, a majority of visitors are white, and minorities may feel unwelcome or uncomfortable when visiting. The Institution of Contemporary Art (ICA), located in the Seaport neighborhood of Boston, is an example of a museum intentionally placed in a wealthy area so that more affluent people will visit. In fact, the ICA existed in various locations in the past, but when they moved to the Seaport location, the number of visitors increased tenfold. Museums are also largely segregated due to the high prices that they charge. The Museum of Fine Arts charges adults an admission cost of $25 and the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum charges adults $15, which is prohibitive to even an average Boston wage earner. The Boston Globe confronts this issue of unfair pricing as part of their seven-part series BOSTON. RACISM. IMAGE. REALITY. In this series they answer the question “Does Boston still deserve its reputation as a place unwelcoming to blacks and why? Also – how can the situation be improved?”

My walking tour will illustrate just how museums can be related to racism in our city. How they have the power to either divide or link present and future communities, the control over whether or not minorities feel comfortable visiting their exhibitions, and the influence to decide whether or not they feature art from minority cultures. Some museums are making the effort to welcome diversity and have programs set in place to expand their cultural inclusion. The MFA has responded with the creation of the program “Toward a More Inclusive MFA.” The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has responded with their collaboration with Indigenous artists from Native American tribes on Indigenous People’s Day. During my research for my walking tour, I learned the ways that museums have divided communities but also how they can rebuild links and be more inclusive of minority communities. Reflecting on Degas’s quote, museums need to be held responsible for how they make others may see.