Reflective Essay

My Emerald Necklace Transect project on Boston’s failed Olympic bid was inspired by the article “For blacks in Boston, a power outage” in the Boston Globe’s 2017 Spotlight Series titled Boston. Racism. Image. Reality. This article examined the Olympic bid from the perspective of the racial and power imbalances it represented in the context of the city of Boston, which was intriguing to me because efforts to bring Olympics to cities are often regarded as beneficial for large-scale and long-term urban renewal, which was not the case in Boston.

The Olympic bid has its roots within an unprecedented and rare shift in Boston’s rigid political power dynamic: the 2013 mayoral election following Thomas Menino’s announcement that he would not be running for re-election and ending his term as Boston’s longest-serving mayor. The 2013 election between Marty Walsh and John Connolly would thus elect Boston’s “first new mayor since 1993” (Dempsey & Zimbalist 1). However, despite the fact that Boston’s mayors (though few and far between) have historically enjoyed an inflated level of power, the vacuum created by the mayoral transition led to a flurry of activity to devise an Olympic bid from the city’s most influential figures. According to the Globe’s analysis, “legal documents made it clear who was in charge: five prominent executives from the region's dominant spheres of influence, representing business, higher education, sports, and construction,” all of whom were wealthy, white men who had been long ingrained in Boston’s power structures via their political, financial, and social capital (“For Blacks in Boston 1). This was notable because it implied that the Olympic bid would inherently appeal to the business-driven interests of these powerbrokers (as they came to be known) rather than the nearly 670,000 Bostonians who would ultimately see the effects of Olympic developments in their backyards. Furthermore, it emphasized the secrecy and non-transparency that undermined Boston’s bid, a blunt reminder of the city’s “insular power structure,” as the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team refers to it (“For Blacks in Boston” 3). Among these powerbrokers, John Fish, a competitive developer known as the “the dominant builder in New England”, emerged as a clear leader and a key planner of the ways in which the Olympic bid would impact Boston’s built environment (Dempsey & Zimbalist 1).

Fish and his colleagues had grandiose visions for Olympic venues that would simultaneously highlight the best of Boston’s historic charm, as well as incorporating new construction (such as the Olympic Stadium, Athletes’ Village, and other sports facilities) that would facilitate urban renewal while simultaneously turning people like John Fish a profit by increasing the cost of Boston’s already expensive land and displacing the city’s residents.

Additionally, Fish worked hard to insulate his power by surrounding himself with like-minded individuals. Specifically, he himself served as the chairman of the bid’s exploratory committee, where he appointed business elites to serve alongside him and ignored the “long list of professors and academics with the experience and expertise to weigh the costs and benefits of a potential bid,” which was available to him given Boston’s rich network of intellectuals (Dempsey & Zimbalist 1). Thus, there was never a proper economic analysis of what the Olympic bid would actually cost the city, nor was the long-term sustainability of Olympic-related development ever considered, as the venues proposed by Fish’s team remained rosy visions of a plan that could never actually be realized.

Nonetheless, these visions carried clout and were not opposed by the higher echelons of Boston’s society simply because the power of the people behind them served as justification. As an added dimension of unfairness, Bostonians were promised that their taxes would not pay for budget overruns affiliated with Olympic construction: a promise that was never guaranteed in the first place, and was ultimately reneged on due to a lack of foresight, or perhaps simple ignorance on behalf of Fish and his cronies.

Given this background of Boston’s Olympic bid and the web of power behind it, it becomes fascinating to explore the bid and the opposition it faced as a series of relational and racialized landscapes in order to understand why it eventually failed. No Boston Olympics, which was the group that championed the opposition to the bid, represents a continuation of Boston’s spirit of urban activism which has been advocating for the rights of citizens ever since the times of the American revolution. “Naysayers, after all, helped make Boston the city it is,” writes Joan Vennochi of the Boston Globe (Vennochi 2). This spirit of activism is also what kept I-95 from razing Roxbury in the 1960s, when concerned Bostonians rallied against the city’s spirit of urban renewal to preserve their built and natural landscapes from being flattened by a highway, as Karilyn Crockett notes in her book, People Before Highways (Lovett 2:32-3:00). Thus, this notion that urban spaces should serve the people first and foremost has been a resounding aspect of Boston’s history, and has certainly contributed to shaping its landscapes today, especially in the context of the Olympic bid, where this mindset prevented such a drastic and expensive transformation of the city’s built environment.

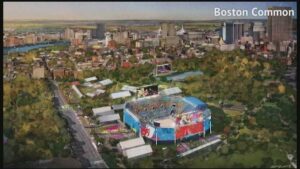

The Emerald Necklace, which was Frederick Law Olmsted’s original blend of Boston’s natural and built environments, is another key relational landscape related to Boston’s Olympic bid. The Emerald Necklace was well-integrated into the bid’s original plan, as two of the venues were located directly in Emerald Necklace parks: Boston Common and Franklin Park. Although this certainly serves as a connection between Boston’s history of landscape architecture and the modernity that the Olympics would bring to the city, there are greater implications to these Emerald Necklace sites being utilized as Olympic venues. Namely, it brought about concerns related to the accessibility of the park for public use following the conclusion of the Olympics. Olmsted’s original plan intended for these parks to serve as refuges from the urban clamor, designed to be accessible to Bostonians of all races, classes, and genders. However, making them home to Olympic-grade stadiums and athletic facilities would not only detract from the peace and serenity within these parks, it would also detract from their history as Olmsted’s lasting contributions to Boston’s landscape. Furthermore, the use of public parks for Olympic venues is contradictory as it commodifies a space that was intended for free use, and which implies the potential to extend this commodification into the city’s post-Olympic future as it blurs the lines between public and private land. This is especially pertinent when considering the power-hungry, competitive individuals like John Fish, with direct ties to real estate, who were driving the bid.

Franklin Park, an Emerald Necklace site and the starting point of my tour of Olympic bid venues, also serves as an important racialized landscape in the context of the bid. The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Series points out that “other than Franklin Park, the Games would not include another venue in the city's predominantly black neighborhoods (“For Blacks in Boston 3). This was a fundamental way in which the built environment envisioned for Boston’s Olympics fostered exclusion, and was overall indicative of the “diversity problem” that was present from the very outset of the bid’s planning process (“For Blacks in Boston 5). The racial implications of the proposed Olympic venues were further made clear through the other locations featured in this Emerald Necklace Transect, namely through their division into a “waterfront” and “university” cluster, which would embody Boston’s gentrified Seaport neighborhood, and Boston’s prestigious institutions of higher education which, to this day, remain institutions that cater to a majority of white, wealthy students. Ultimately, by examining Boston’s Olympic bid through the lens of its impacts on the city’s built landscape, it is evident that inclusion was never a goal for the bid’s developers, and it would become a project of the white and wealthy, for the white and wealthy.

Works Cited

Dempsey, Chris, and Andrew Zimbalist. “The inside Story of No Boston Olympics.” CommonWealth Magazine, 27 Apr. 2017, commonwealthmagazine.org/economy/the-inside-story-of-no-boston-olympics/.

"For Blacks in Boston, a Power Outage: Political and Civic Clout here Remains the Near-

Exclusive Preserve of White Residents. and there are Few Signs Now that this Picture

Will Change."Boston Globe, Dec 15 2017, ProQuest. Web. 3 Dec. 2020 .

Lovett, Chris. “How the People Detoured the Highway.” YouTube, YouTube, 15 May 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdOVj0BT2IQ.

Vennochi, Joan. “No Boston Olympics Activists Are Heroes - The Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com, The Boston Globe, 28 July 2015, www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2015/07/27/joan-vennochi-boston-olympics-activists-are-heroes/4As27xAFegVIHwrZz4IiwI/story.html.

A rendering of the proposed Athletes' Village at Columbia Point in Dorchester

An aerial view of the proposed Olympic Stadium at Widett Circle, looking towards the city and Fort Point Channel